Atum

Who is Atum?

Atum (often written ỉtm, itmu, or Tem/Temu in older transcriptions) is the self-generated creator god of the Heliopolitan cosmogony. His name is commonly glossed as “the All,” “the Complete One,” or “He who is finished/complete,” reflecting a core idea: Atum embodies totality within himself before creation differentiates into many parts. In Egyptian thought, “creation” is not a one-time event but an ongoing emergence of order (maʿat) from potential chaos (isfet). Atum is the first articulation of that emergence.

In mythic narrative, Atum arises on the primeval mound (the benben) out of Nun, the boundless waters of potential. He brings forth the first divine pair—Shu (air/space) and Tefnut (moisture)—through an act that Egyptian texts describe with frank physicality (spitting, sneezing, or self-fertilization). From Shu and Tefnut come the sky (Nut) and earth (Geb), and then the famous divine siblings Osiris, Isis, Seth, and Nephthys. In this way Atum is the progenitor and unifying principle of the Heliopolitan Ennead (“the Nine”).

Atum is also strongly identified with the sun in its evening aspect—as the sun that “finishes” its course and returns to the horizon. In this form he is often called Ra-Atum, emphasizing a cycle: Khepri (the becoming sun) at dawn, Ra at midday (the manifest sun), and Atum at sunset (the completed sun).

In what era did Atum “exist” (historically speaking)?

As a deity of Egyptian religion, Atum is attested very early. He appears in the Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom (circa 24th–23rd centuries BCE), which are the oldest extensive religious writings from Egypt. These texts already present him as a creator and father of the Ennead. That said, cultic ideas often predate their written attestations, so Atum’s worship is plausibly older than the earliest inscriptions we have.

Across the Middle Kingdom and into the New Kingdom, Atum’s role remains robust—especially in Theban inscriptions and temple scenes that invoke the great gods of Heliopolis. In later periods (Late Period through Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt), priests and scribes continue to integrate Atum into sophisticated theological syncretisms. He remains a key element of temple theology and hymns, frequently in the compound identity Ra-Atum. The persistence of his cult across more than two millennia shows how foundational the Heliopolitan creation story was to Egyptian religious imagination.

Is Atum the same as Adam?

According to the accounts of Egyptologists, they confirm that:

No, Atum and the Abrahamic figure Adam are not the same, historically or conceptually.

Different cultures and languages:

Atum belongs to ancient Egyptian religion (Afroasiatic culture with its own language family and writing systems)

Adam is a Muslim-Christian-Hebrew/Abrahamic figure rooted in Semitic traditions. He is believed in by all Muslims, Christians, and Jews – the Abrahamic religions.

Different roles:

Atum is a god—the self-created creator and progenitor of other gods. Adam is a human—the first man in the Genesis narrative.

Different cosmologies: Atum’s creation is a self-emergence from watery Nun and a generation of deities culminating in an Ennead. The Genesis creation is an act of a transcendent God who creates by command; Adam is formed from dust and animated by breath.

Similar-sounding names sometimes lead to comparisons, but the etymologies, mythic functions, and religious frameworks are unrelated.

Temples and places where Atum’s name is mentioned

Atum’s principal home is Heliopolis (ancient Iunu; Egyptian Ỉwnw; Greek Heliopolis, “City of the Sun”), in the northeastern Nile Delta (near modern Ayn Shams/Matariya in Cairo). Heliopolis is the theological cradle of the Ennead; its temple complex centered on the benben stone and the obelisk as solar symbols. Within this cult center, Ra-Atum receives worship as a creator and as the sun in its “complete” aspect. Even though the standing architecture of Heliopolis is largely lost, texts and later references make its prestige unmistakable.

Beyond Heliopolis, Atum’s name and images appear widely:

- Per-Atum (“House of Atum”) in the eastern Delta—often identified with Pithom in later sources—was associated with the god’s cult. Archaeological identifications center on sites such as Tell el-Maskhuta (and historically also Tell el-Retaba/ Heroonpolis) where late-period inscriptions and monuments reference Atum.

- Sun temples of the Fifth Dynasty near Abu Ghurab celebrate the solar creator (primarily Ra), but theology often treats Ra and Atum as a continuous solar identity—so hymns and inscriptions link Atum closely to these solar cults.

- Memphis and Saqqara: State cult inscriptions, royal funerary texts, and later temple reliefs invoke Atum among the great gods; shrines and chapels inside larger complexes could be dedicated to him or to Ra-Atum.

- Theban temples (Karnak, Luxor, and west-bank sanctuaries): Hymns to the sun god frequently include Atum in enumerations of creator forms (Khepri–Ra–Atum). Individual shrines to Atum existed within larger complexes in various periods.

- Other Delta centers: Atum appears in lists and scenes as part of the Ennead venerated in places like Tanis and Bubastis, reflecting the spread of Heliopolitan theology.

Two clarifications help avoid confusion:

- Dedicated temples vs. mentions: Many temples across Egypt reference Atum in hymns and scenes without being primarily “his” temples. The Egyptian temple was a theological cosmos, so creators (including Atum) routinely appear even when the main deity is another.

- Place-names: Egyptian toponyms often preserve deity names. “Per-Atum” is a classic example; it signals a local institution of Atum’s cult and may appear in inscriptions even if surviving architecture is fragmentary.

The family tree of Atum’s descendants (the Heliopolitan Ennead)

The Heliopolitan cosmogony proceeds in generational waves from Atum:

- Arum self-generates on the benben, bringing form out of formlessness.

- He creates the first pair:

- Shu (air/space), who separates sky and earth.

- Tefnut (moisture/condensation), balancing dryness and wetness.

- Their children are:

- Geb (earth), the fertile ground.

- Nut (sky), the arched firmament who daily births the sun.

- From Gab and Nut come the divine siblings:

In many formulations, Horus (the royal falcon) is the son of Osiris and Isis and completes the divine polity, though he is sometimes counted outside the “Nine.” The Ennead is as much a theological map as a family tree: it orders the world—space, moisture, earth, sky, life, death, kingship—under a genealogy anchored in Atum’s initial act.

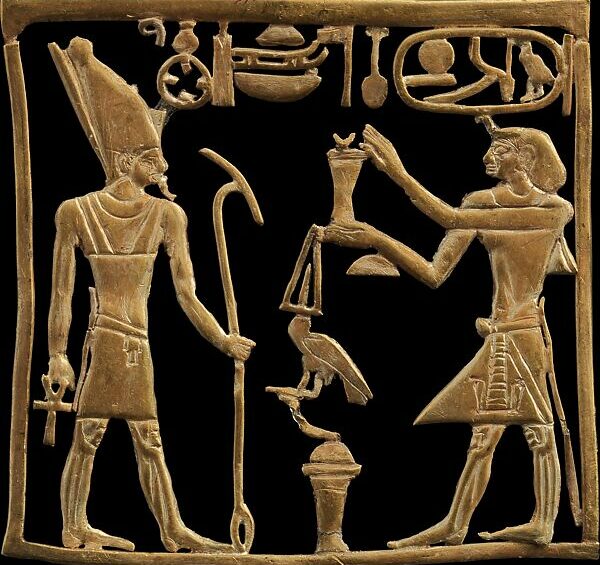

Symbols and iconography of Atum

Atum’s visual and symbolic repertoire is rich and deliberately layered:

- The Setting Sun: Atum is the evening sun. In hymns, the sun’s daily journey is a life cycle: Khepri (becoming) at dawn, Ra (manifest power) at noon, Atum (completion) at dusk. This encodes a philosophy: creation is cyclical, ever-renewed yet always tending toward wholeness.

- Double Crown (Pschent): Atum frequently wears the red-and-white crown of Upper and Lower Egypt. As a creator and patron of kingship, he embodies unification and cosmic completeness.

- Human Form—Elder or Perfected Man: Unlike animal-headed deities, Atum is often shown as a man, sometimes with the double crown, emphasizing completeness and sovereignty.

- Serpent Form: In cosmogonic and eschatological texts, Atum can appear as a serpent, a form associated with primordial potency and with the end of the cosmic cycle when creation returns to Nun.

- Benben and Obelisks: The primeval mound’s tip (benben) and obelisks are solar-Heliopolitan symbols connected to Atum’s first emergence.

- Bennu Bird (phoenix-like): While more directly linked to Ra and temple theology at Heliopolis, the Bennu’s cyclic self-renewal complements Atum’s identity as completion within cycles.

- Was-scepter and Ankh: As with many gods, symbols of power (was) and life (ankh) appear in Atum’s hands, underlining creative authority.

What did Atum represent to the ancient Egyptians?

Atum is the philosophical heart of a distinctive Egyptian insight: the world is an ordered unfolding of potential, and that unfolding is cyclical, not linear. He represents:

- Self-origination and Totality: Atum is “complete” in himself. Before he makes anything, all things exist in him virtually. Creation is emanation and differentiation.

- Cosmic Kingship: As father of gods and guarantor of order, Atum is a model for human kingship. Pharaoh’s unifying role echoes Atum’s gathering of the world’s parts into a coherent whole.

- Cyclical Time and Eschatology: As the evening sun, Atum manifests completion and return. Some funerary compositions envision a distant end to the current cosmic cycle when Atum will dissolve the created order back into Nun and remain with Osiris in the waters—after which creation begins anew.

- Balance and Continuity (Maʿat): Atum’s work is not merely to start the cosmos but to maintain its intelligibility. Daily rituals re-enact creation to keep chaos at bay.

- The Bridge between One and Many: Egyptian religion harmonizes multiplicity (many gods, many forms) with unity. Atum, as the “Complete One,” is a theological anchor for unity without erasing the many.

Places of worship and cult

While Heliopolis is paramount, the idea of Atum permeates Egyptian religion:

- Heliopolis (Iunu): Principal cult center with the benben, solar obelisks, priestly colleges (notably the “Great House of Ra”). Hymns invoke Atum as creator and evening sun.

- Per-Atum (House of Atum) in the eastern Delta: A concrete institutional locus for Atum’s worship; the name itself attests to ongoing cult activity.

- Royal Sun Cults of the Old Kingdom: Fifth Dynasty kings built solar temples celebrating the sun’s creative power; Atum pairs closely with Ra in these cults.

- National Temples and State Ritual: Large complexes (Memphis, Thebes) included shrines and chapels where creators—Atum among them—received offerings, especially in cycle-of-the-sun rituals.

- Funerary Contexts: Pyramid Texts, Coffin Texts, and the Book of the Dead invoke Atum in prayers for rebirth and safe passage. The king, and later non-royal elites, participate in the daily solar cycle; to be aligned with Atum’s completion is to hope for one’s own completion and safe return.

Atum and “the Trinity”

Egyptian religion does not have a fixed single triune doctrine comparable to later theological “Trinity” concepts, but triads are common in local cults (e.g., Theban: Amun–Mut–Khonsu; Memphite: Ptah–Sekhmet–Nefertem). In Heliopolis, the creative logic naturally forms a triadic pattern:

- Atum (the self-complete source)

- Shu (space/air)

- Tefnut (moisture)

This first triad expresses how undivided completeness produces a paired world through differentiation. From there, Heliopolis favors the Ennead (a ninefold), not a single exclusive triad, but hymns sometimes single out Atum with Shu and Tefnut to highlight the shift from unity to duality and then to generative multiplicity. In solar theology, another meaningful triad appears: Khepri–Ra–Atum, mapping becoming, presence, and completion across the day.

Atum and Khnum

Khnum, a ram-headed god centered at Elephantine and Esna in Upper Egypt, is likewise a creator—but in a different key:

- Atum creates by self-generation and emanation, bringing forth deities who structure the cosmos.

- Khnum creates form—fashioning humans (and sometimes gods) on his potter’s wheel, shaping bodies and their ka (vital essence). He is intimately connected to the Nile’s inundation and to fertility via the life-giving waters.

Rather than competing, these models complement each other. Atum’s cosmology explains the origin and order of the world; Khnum’s craftsman imagery explains the formation of individual beings within that world. In temple hymns and theological treatises, Egyptian priests are comfortable layering these truths: the cosmos can be both an emanation from a self-complete source and a crafted artifact shaped with care. In some later texts and local theologies, Atum and Khnum can be invoked together or appear in the same ritual horizons, but widespread direct syncretism (a fused compound deity) is far less common than, say, Ra-Atum or Amun-Ra.

Atum and Osiris

Osiris is Atum’s descendant through Geb and Nut, and he personifies fertility, kingship, death, and resurrection. Their relationship works on two levels:

- Genealogical: Osiris is part of the Ennead that Atum generates; thus the Osirian cycle (death–dismemberment–reconstitution–rebirth) depends on the cosmic order Atum initiates.

- Eschatological and Ritual: In certain funerary spells, Atum promises that, at the end of a cosmic cycle, he will reabsorb creation into Nun and remain with Osiris in the waters. This startling idea shows how Egyptian theology integrates creator and resurrected king: creation, death, and renewal are woven together. Osiris’s triumph over death becomes the pattern by which humans hope to be renewed, and Atum’s power grounds the cycle’s cosmic scope.

In daily cult, Osiris’s rites (especially at Abydos and in Theban temples) are distinct from Atum’s solar rites, yet the two gods collaborate metaphysically: Atum secures the framework of order; Osiris guarantees renewal within that framework.

contact us to explore the beauty of ancient Egyptian civilization.

Atum Trip will provide you with more plans and options for your visits.